Since starting my new career, I have read a lot of business- and leadership-related content. One idea that has popped up several times is that of a "keystone," or the single most important activities related to your field. In my area of law, reading new caselaw and networking are those activities. I can have the best precedent documents and write amazing emails and have a killer support staff, but none of that matters if I don't know the law and don't have clients to serve. Time spent here is never wasted.

In chess, and likely most other fields, a similar dynamic applies. There are dozens of things that affect our game and influence our result, but a core few influence the vast majority of our games. It's not hard to guess, either. It's calculation. GM Shankland, 2700+ grandmaster and author and top 22 or so in the world, says that nothing else matters until about 2300 Fide.

In a previous blog post on 80/20 chess training, I suggested that calculation should be a mainstay in your chess training. Duh. Today, I want to focus solely on calculation training and emphasize the training aspect. That is, there's a difference between doing calculation and training it. This will explain that difference and give a guide path on what to do next.

The Difference

There's a difference between training something and simply doing that thing. The easiest example is handwriting. You've likely written something every day of your life since you were a kid, and yet your handwriting hasn't steadily improved. You have literally hundreds of hours of doing handwriting, but zero improvement, even though your handwriting is not perfect. I mean, I assume. My handwriting certainly qualifies.

|

| Definitely NOT Smithy's handwriting. |

This applies to anything. You want to run a faster 5k? Going out and running 5k will definitely help ... to a point. Simply running more, though, will level off. If you are serious about running faster, you would follow a 5k training plan, which would include different workouts, different tempos, have graduated difficulty, etc. This might involve running more than 5k on certain days, while others you run less. That seems counter-intuitive, but these training plans work.

Pick an activity. Golf? Yup, playing golf will improve your skills ... to a point. Specific training on individual skills is needed for serious results. Swimming? Yup, doing laps will help, but taking lessons on proper technique and doing specific workouts will help more. Chess? Yup, same thing.

Indeed, there are people that have gotten quite good at chess just by playing. They put in dozens if not hundreds of hours, they get exposure to different practical positions, they put in quality time and they get results. There's no argument, though, that specific training on core skills, to hone them and make them more effective, will improve those results even more. And the ultimate skill, of course, is calculation.

Calculation as a Keystone

In a previous post, I argued that "calculation" is really a collection of smaller sub-skills: board vision, pattern recognition, combinations and raw calculation. While all our important, the first two disproportionately decide beginner and intermediate games, whereas the later two matter much more for advanced players. These sub-skills should be treated separately.

First, Board Vision

By this, I mean literally seeing the threats and capture possibilities on the current board. Sometimes we experience chess blindness, where there is a hanging piece, a one-move capture, and we completely miss it. This is failure of board vision. Many beginners live in a perpetual semi-blindness, where a mental fog obscures the board. Such one-move mistakes riddle their games, and improving this sub-skill is the single most effective thing they can do to improve their results.

|

| We've all been here... |

How to Train This: Most people learn this by default, simply by playing lots of games. That's not training, though. Doing lots of tactical puzzles helps, but that focuses more on the pattern recognition aspect we will cover next. De la Meza, in his controversial book "Rapid Chess Improvement," provides some vision exercises, though I've never read it and have only heard this from others.

Here's how I trained this: I would review a game and ask, on every single move, "what has changed in this position?" For example, in the starting position, 1.e4 controls d5 and f5 and opens up lines for the Queen, Bishop and gives e2 for the Knight and King.

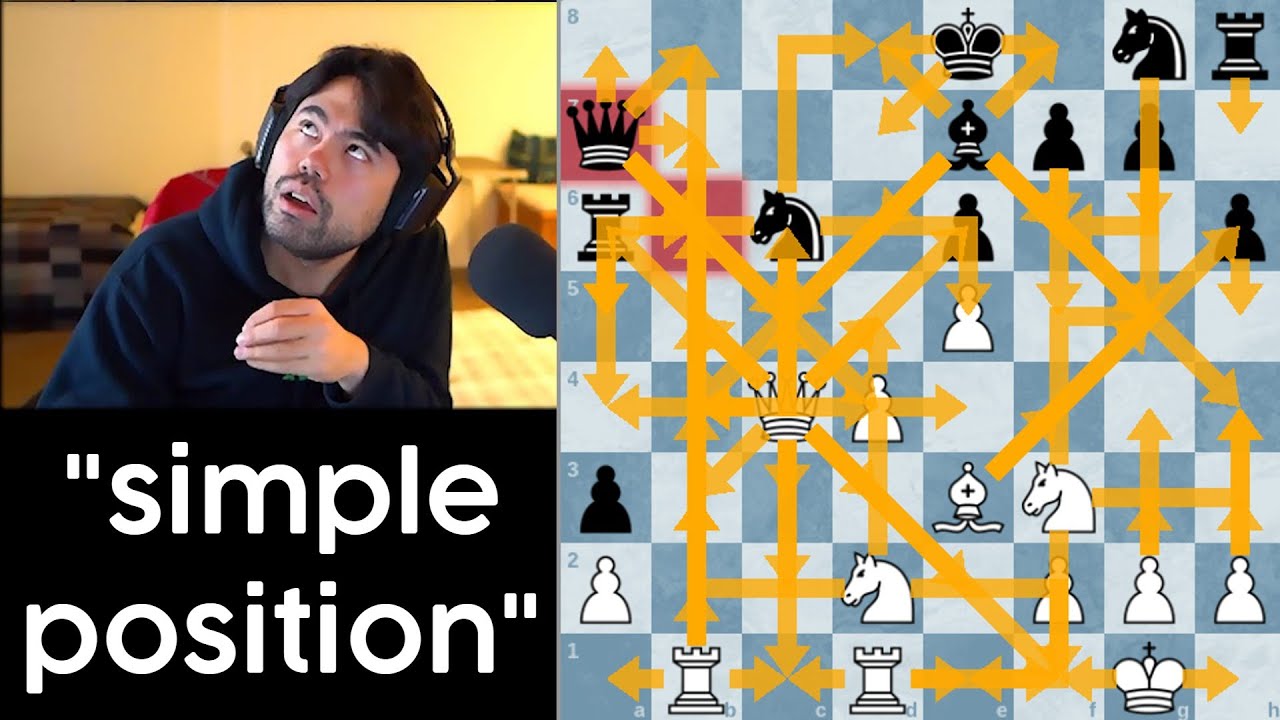

You then do the same thing for Black's move, and you repeat for every move of the game. I was not focusing on the game in any way: not evaluating the position, not looking for tactics, not calculating variations. Instead, I was solely focused on seeing the board in front of me. I was simply trying to see what had changed in the position, and I found physically drawing the arrows on the board really helped.

Another, similar exercise is to take random middlegame positions and then, for one side, literally look where all the pieces can go. Do it systematically, starting with the most valuable pieces and move down. So the King can go xyz, the Queen can to abc, etc etc. Then skip to another position and do the same thing. Again, drawing the arrows really helps.

For a visual explanation, I explained the first exercise in this YouTube video and the second one here. The second one was part of an unreleased project that has since stalled out. Curious if people have any thoughts or feedback about the concept.

The Goal: You know your board vision is improving when you can look at the board and have the various threats jump out at you. It requires no effort. That's the goal. If it takes mental effort to see one-move threats literally right in front of you, then you have no chance at seeing multiple moves ahead. That's why this is the foundation, and for rank beginners and those lower than 800 elo or so, it might be the best use of your chess time.

In my case, I did this consistently for about two weeks, give or take, and drastically reduced my blunder rate. It has paid off immensely.

Pattern Recognition

Once we start seeing the individual moves clearly, we can now focus on patterns, on the common motifs that occur again and again. Forks, pins, skewers and the other common tactics. Similar to board vision, our goal isn't just to see these, but to have them jump out: you look at this position and Bb5!, pinning the Queen, is the first move that comes to mind.

How to Train This: This is well-known. Do lots of easy tactics. Lots. You want to do hundreds of puzzles for each theme. Start with the most common ones: forks and pins occur far more often than decoys or interference, so do those first.

These puzzles should be easy. That means 2-3 moves max. There should be nothing complicated: you look, you see a potential fork, you play it, you win, next. You don't so much need to think about it as you need to see it. Once this becomes automatic we can get to more complicated examples, but build this base foundation first. Once a particular motif starts feeling comfortable, switch to another one.

I would strongly suggest that you train by THEME, not via random puzzles. Learn all the themes first, get good at them, and then start training random puzzles. That said, you can do random puzzles as a warm-up or as a way to keep your other skills sharp, but in terms of pattern recognition training, which is our goal here, focus most of your time on individual themes first.

All the major chess sites let you train by theme. Lichess and ChessTempo let you do it for free, but it's harder to force these systems to give you easy puzzles; as you solve more, you get a higher rating and thus harder puzzles, which isn't what we want. It may take some fiddling around with settings to get these to work as intended.

It may be useful to purchase a beginner's tactics book for this purpose. For example, Chess King has a Beginner's Tactics Course that costs $12 and contains 4,000 exercises and over 1,800 Knight forks. That's an incredible cost-to-tactics ratio. Chess King looks like a dodgy site, and it's interface definitely shows signs of age, but looks are deceiving: the content is incredible. I'm not necessarily recommending this course, merely listing it as a low-cost example.

Combinations

I've dividing this sub-skill into two-related parts, though they are arguably the same thing. First, harder puzzles, so instead of a 2-3 move fork puzzle, it will be 4-5 moves. Second, combination of themes, so using a pin to set up a fork, for example. Effectively, these will work out to the same thing: the only reason a puzzle requires 4-5 moves is because there are multiple factors and motifs at play. The chess world has a very specific definition of "combinations", though, so I thought I better make this distinction up-front.

How to Train This: It's actually quite simple: keep doing what we were doing before, but with harder puzzles. It probably makes sense to use the "random" puzzle feature now, though training very hard forks and pins will also work, with "very hard" being relative to your level.

The focus changes, though. Before, we were training our sight, on seeing these most fundamental threats and patterns. Now, the patterns are more hidden and puzzles are more demanding. The solution will not simply jump out, so we need to focus on the correct process of calculation.

Start with the forcing moves, so checks, captures and threats, and after every forcing move, see if you have more forcing moves. If one check leads to another, investigate. It might lead to mate. If it doesn't, oh well, check the next forcing move, and so on and so forth until it becomes a habit. As you do this, you will uncover the solution, one step at a time.

Again, the focus is on the correct process. Don't just guess, don't play moves randomly. A random process leads to random results. Check the forcing moves, and start with the most forcing (checks) and work down to the least forcing (threats). We want to make this a habit, where you look at any given position and your mind immediately points out all the forcing moves. That is the goal.

This bears repeating: in the earlier examples, the focus was on seeing the right move. Getting the puzzle right quickly was the goal. Here, getting the puzzle right quickly is not the goal. That's nice, but it's not the main thing. Focus on the process. Do it right, every single time. No shortcuts. Make it a habit.

Raw Calculation

This basically takes the last step and makes it more extreme. Take the hardest positions you can find and calculate as deeply as can. Check all the moves, all the relevant replies, all the different move orders. Tax your brain. Then check the answer, see how you did and see where you can improve.

That's basically it. If you have followed all the steps, then this won't be easy (of course not, that's the point), but it will be possible. You will have the requisite board vision and a large collection of patterns to rely on, and you've established the habit of checking forcing moves. Most raw calculation positions are just an extension of this.

How to Train This: The standard advice is to take very hard puzzles, or even composed studies, and just dive in. Don't move the pieces; do everything in your head. Don't give up. If it takes 30min, then it takes 30min. Just get it done.

Personally, I often put a 10min time limit on positions. If I'm still stuck after ten minutes, it's probably more time effective to check the solution and see what I missed rather than beating my head against the proverbial wall. I don't do this consistently, though, and there's a certain rush of struggling with a puzzle for 25min and then, almost magically, finding the solution. That gets seared into my brain and I never forget it. Both approaches work.

GM Surya Ganguly has suggested to train on non-puzzle positions. So take a random complex middlegame and just sit with it for a long time, deeply calculating as far as you can. Because these are not puzzles, it trains our skills just like in a real game, as we won't know if there is a tactic ahead of time. He also suggested to see "two more moves ahead". So, if you would normally stop after four moves in an unclear position, force yourself to go two moves more (eg, one move for each side, or 2-ply). That will really stretch your abilities, and when it starts becoming easier, look further ahead.

GM Igor Smirnov has stressed the importance of doing it in the right way. If it takes you 20min to solve a puzzle, but the solution was relatively simple and should have taken 5min max, you need to figure out what you did wrong and change it. Did you not consider a candidate move? Overlook a reply? Not see a potential pin or fork? Identify the issue so you can fix it. If you didn't consider a candidate move, then in your puzzles you focus extensively on candidate moves to fully ingrain it. Even re-do the puzzle with the right candidate moves in mind, just to reinforce how you should have solved it.

Focus on doing the process right. Getting the answer right for the wrong reason isn't improving our skills. That's the lesson we are trying to learn in this latter phase. If we do things in the right way, results will come.

Conclusion

Calculation is the prime skill in chess, and the above summary provides a guideline on how to get better at. At the end of the day, there's nothing complicated about it. I haven't said anything groundbreaking here. It's simply a question of putting in the work. That's the hard part. It's easy to say, not so easy to do.

I'll also add that our ego can be the enemy. It's tempting to think we are too advanced for the earlier steps and skip to the harder sections. That's how we tend to get stuck. Over the last few months, I've been training my pattern recognition, and I've noticed some rather embarrassing gaps. I have spent 30+ seconds looking at mate in 1s or other elementary patterns. I want to focus on raw calculation, but doing work here is probably more beneficial and paves the way for smoother results.

No comments:

Post a Comment