Let's now flip the script: how do you get better at chess? Two things stand out. First, there is a wealth of chess content that teaches us something about chess: openings, endgames, concepts, ideas, traps, the list goes on and on. I call this, broadly speaking, chess knowledge. Second, we can take what we know and apply it: playing games, analyzing, calculating puzzles, that sort of thing. For lack of a better term, I call this chess skill.

More than just nomenclature, I believe this is a crucial concept for improvement. Indeed, it may be the most important element when it comes to improving. I think the majority of players, and I point to myself here, spend far too much time on knowledge acquisition when we should be focusing on building our skill.

Knowledge is Easy, Skill is Hard

We love acquiring knowledge. It feels so good. Whether you open a book, watch a video or play through an app, you get that instant rush. The answer is presented to you, clean and polished. With videos in particular, nothing can be easier: sit back and relax as an expert tells you what you should be doing. And it works! You can often apply what you learned in your next game, especially if it is an opening trap. When it works, you win without even needing to think. Nothing can be easier.

In contrast, skill work takes effort. You are given a messy middlegame position with multiple good-looking moves. Which move do you start with? How deep do you calculate? You might spend 10min never making a move, just staring at the board, sweat rolling down your face as you sink deeper into thought. Few things in chess are harder, and even if you get the right answer, you will never have that same situation in your own game. You'll never use what you just learned, at least not directly.

We love knowledge. That's why people sell it to us. There's ten opening courses for every tactical course. "Learn this and crush 1.e4" sells a lot better than "Put in the hard work and you will probably get better." As such, if we spend time on chess products, especially modern products, it is almost certainly a knowledge-based product.

That isn't necessarily bad, but it runs into a problem.

Knowledge Reaps Diminishing Returns

In math, we learn the times tables, and it really helps. 8x9 = 56. You just know that. No thinking required. Eventually we start finding 12x18 in our books. That's a pain in the butt, and a lot harder to memorize. Flip forward a few more pages and we get 1289x7452.

Now we see the problem: we cannot possibly memorize everything. There's literally too much to know. This does not mean that learning the times tables was a waste of time. On the contrary, it sets a wonderful foundation and makes so many things easier. At some point, though, we need to move beyond memorizing every math fact and learn to do math, practically speaking.

The same is true for chess. Our first taste of chess knowledge gives us a massive boost. We now know about space and time, how knights are worth 3 and rooks are worth 5. We learn to develop in the opening and promote pawns in the endgame. We learn the most common plans and how to take advantage of common mistakes. Our game flourishes.

Soon, though, we get to the chess equivalent of 12x18, where we learn stuff with little practical value. Indeed, many of us are closer to the 1289x7452 example, where we learn an opening line 18 moves deep ... and never get to play it once in our life. We learned it, but it has zero impact on our results.

Even if we avoid that extreme, it still does not escape from the conclusion: we eventually reach a point where learning more about chess does not help (or only helps a small amount) with chess improvement. We need something greater. We need to learn how to do chess, practically speaking.

Skill Sets the Stage for Sustained Success

What is math skill? Basically, given a math problem, can you find the right answer? If so, you have some skill. Memorizing the times tables helps, but real improvement comes from learning the right METHOD and then doing LOTS of practice problems. That is, with 1289x7452, you don't just guess. You learn how to solve these sorts of problems, and then do that lots of times until it becomes a habit.

| We might need to practice with simpler examples first, but the overall METHOD stays the same. |

I would define chess skill as basically the same thing: given a certain position, can you find the best move? If you can do that for lots of different positions, you are good at chess. How do we do this? By following the right method and getting lots of practice.

By "method", I'm referring to something like the thinking system article I wrote about earlier. Many of us do this instinctively: when we see an exposed King, we immediately look for checks, captures and threats. In the opening, our first thought is developing and castling. It doesn't matter if we play a different opening, our method, our mode of thinking, is still the same.

More fundamentally, though, it comes down to practice. Look at a position and find the best move. The more you do that, the better you get at chess. It really is that simple... okay, maybe not...

Developing Skill

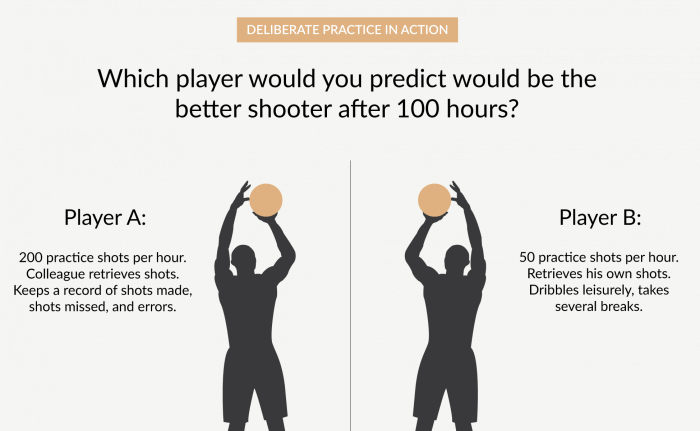

The personal development literature talks about 'deliberate practice' as the best way to develop skill (in general, not just in chess). Rather than mindless repetitions or going through the motion, deliberate practice involves breaking a skill into its component parts and aiming to improve each aspect. James Clear's website gives the following example:

|

| https://jamesclear.com/beginners-guide-deliberate-practice |

"Chess skill", as I've defined it, can be broken into several component parts:

- raw calculation

- visualization

- pattern recognition

- evaluation

- even softer skills like time management

It's no surprise, but one chess activity improves basically all of these: tactical puzzles. Most of us do tactical puzzles, but do them with deliberate practice in mind? In James Clear's example, do we record our attempts, analyze our mistakes, figure out what went wrong and look to improve it? Or do we immediately click Next and try the next puzzle?

"Guess-the-Move" games also train all of these skills. If you find a game between two masters and literally guess each move, then you are effectively playing against a master. This lets you compare your thoughts and thinking system, your "method", with that of a master player. The closer your moves align, then greater your skill is becoming.

Of course, "guess" isn't the right word. You aren't literally guessing. Instead, you are analyzing the position, looking for threats, calculating moves, doing all the things you would do in a game. When you decide on your move, you compare it with the game. The more you do it, the more you will start thinking like a master.

Finally, analyzing your games perfectly maps onto the idea of deliberate practice. First, you use your normal thinking process, your "method", and try to find the best move in each position. I assume you try to find the best moves when you play, yes? Afterwards, you look at what you did right and what you did wrong. Figure out why you got it wrong and then don't do that again, or figure out how you could have got it right and do that instead. The more we do this, the more we are being James Clear's "Player A" and putting in the necessary work to improve our skills.

Conclusion

I am NOT saying that chess knowledge is bad or that you should stop buying courses. I am saying that chess knowledge quickly hits a point of diminishing returns. Learning principles and pawn structures is invaluable; learning the 17th move novelty in the Sveshnikov is almost value-less, at least in terms of helping you improve.

Obviously, those are two extremes. When about the middleground? The answer seems Clear: when in doubt, focus more on the skill-developing activities: calculation, guess-the-move and analyzing games. I've probably spent less than 20% of my recent chess time on those. How much better would I be if that ratio were inversed?

I'm now a lawyer, so I have a great excuse. I come home from work mentally tired. I don't want to do more hard work, so I do some easy chess stuff. There is nothing wrong with that. I can't then turn around and complain that I'm not improving, though. The path to improvement is very simple: calculation puzzles, guess the move games and analyzing every game you play. These things just happen to be the hardest things to train in chess. If I want to seriously improve, I know what I need to do. Until then, I'm fine where I am ... at least for now.

I've mentioned the idea of a "method" numerous times. Let me finish with a quote from the second world champion, which largely inspired this article: "You should keep in mind no names, nor numbers, nor isolated incidents, not even results, but only methods... The method produces numerous results."

It's never a mistake to improve your method.

8x9 is not 56 :-) Anyway, great post as always. If you have not read it already, I recommend Chess for Zebras from Jonathan Rowson. It is a book dedicated to the chess learning process, bad habits, etc., and I think you would just love it.

ReplyDelete