Do lots of tactics. Everyone knows this, and most people spend a fair bit of time doing tactical puzzles on various sites. We reach this annoying place, though, where we can sacrifice multiple pieces for any given solution ... and yet we miss much simpler tactics in our own games. Why is that?

I hinted at this in an earlier post, buy my theory is that people are training tactics incorrectly. Rather, many players are doing tactics, but they are not effectively training tactics. Training entails having a plan. Most people don't have a plan beyond "do a thousand tactics and hope I get better." That might work, but it's slow and inefficient. We can do better.

Today, I will share my thoughts on puzzles: what to do, what not to do, the different types of training and my suggestions on getting started. This post got much longer than I intended, even though, ultimately, I'm not saying anything that the chess world hasn't heard before (easy puzzles for pattern recognition, hard puzzles for calculation). Perhaps my explanations for this will trigger a light-bulb moment or two along the way. One way to find out. Let's go.

Understand Your Purpose

This might sound odd, but why do we train tactics? And why do we train this different from endgames, strategy, openings and everything else? We've all heard that chess is 99% tactics, so getting better at tactics should mean getting better at chess ... but what are we actually doing? What is our end goal?

And don't say "get better at tactics." That's a lousy goal. Be more specific.

In my view, "tactics" encompasses several related and yet distinct concepts. Fundamentally, chess is a game about pieces, and a skilled player can manipulate the pieces to his or her advantage. Every time the pieces interact there are tactics, or, said another way, improving our tactics means improving how we use our pieces.

At the most basic level, we have board vision. This is literally seeing the board. Don't play Rb1, the Bishop controls that square!

At the beginner level, most mistakes relate to board vision. You literally don't see something. This problem continues even into intermediate levels: Example 1, example 2, example 3. Yes, I included one of my games there. The point: all of these are unforced errors, where we drop material to obvious moves simply because the threat was invisible. You quite literally cannot stop what you cannot see. Training tactics helps expand our vision and lower these instances of blindness.

Note that this is distinct from visualization, which is being able to see several moves ahead. Rather, board vision is simply looking at the board as it exists right now and seeing the potential threats and ideas, which squares are safe and which are not, etc. Tactics can improve visualization, though usually it is considered a by-product of training these other concepts.

Next, board vision builds into pattern recognition. Certain piece interactions occur again and again: pins, X-rays, discovered attacks and so on. Recognizing these patterns vastly speeds up our play and allows us to recognize threats much faster, sometimes instantly.

|

| White to move. Probably the most famous mate in 2 from our time. |

When we combine multiple patterns together, we enter the realm of combinations. Admittedly, the line here is a little blurred. Is the Greek Gift a pattern or a combination? I won't decide either way, but there's a clear sense of an increased complexity compared to a standard fork or pin.

Finally, we come to raw calculation. "I go here, he goes there, so I go here, etc." I say "finally", but this underlines the entire process. Even the simplest puzzles involve some element of calculation. Indeed, this is my point: all of these concepts are present when we train tactics, and we need to understand what our focus should be.

Basically, the less complex a position (whether fewer pieces or just fewer candidate moves), the more the emphasis shifts to vision and pattern recognition. More complicated positions focus more on combinations and pure calculation. In general, all elements are present in most puzzles, and it becomes a choice of emphasis. Which one of these do you want to improve?

In general, the simpler positions prepare you for the more advanced ones. As such, newer players should focus on board vision and pattern recognition, and stronger players should focus on combinations and calculation. Again, the word is focus: it doesn't do mean you cannot do the others, but rather you will likely get your most bang for your buck doing this.

Easy vs Hard: Different Ways to Train

With the above framework, the following suggestions should make a lot of sense. Board vision is the most foundational skill. Some positions are simply a question of, "Do you see it?" No amount of calculation will help if you can't see certain ideas. You want the simplest to jump out. For example, take the position after 1.e4 d5 2.exd5 Qxd5 3.Nc3 Qc6:

One move should absolutely jump out at you. 4.Bb5! pins the Queen and immediately wins the game. It's a one mover. You have to see it. If you do, you win the game. If you don't? Then you need to do lots of simple tactics, just one and two move puzzles. Get the reps in to increase these visual muscles.The same thing applies to pattern recognition. Honestly, board vision is basically pattern recognition in its simplest form. Forks, pin, skewers and discovered attacks are just the pieces moving in a certain way. You want to know these like the back of your hand. Like the example above, the answer needs to jump out. If it takes effort to do the easy stuff, you'll never do the hard stuff. How to make it easy? Time and repetition.

Therefore, for both board vision and pattern recognition, you want to get a lot of practice. You want to see lots of different positions and have the right move jump out. Solve easy positions until it happens. Once it becomes too easy, you can ratchet up the difficulty, but always with the aim of seeing these patterns jump out. Spending 10min on one puzzle is a big waste when you can spend 10min on 10 puzzles and get that many more patterns exposed to your brain. Time and repetition are the keys.

In the puzzle above, if that takes you a minute to find 1.Bb5, that's too long. Heck, 15s is too long. Similarly, the puzzle below, you should see it near instantly:

If you don't see it near instantly, then commit to training these simple positions until you do. It's very simple: do lots of 1-2 move puzzles. I mean lots. Hundreds if not thousands of puzzles. Because each puzzle is short, you can do these quickly. Just get the reps in. Once the easy stuff becomes, well, easy, then you can commit to the hard stuff.Board vision and pattern recognition is mainly about seeing what's on the board. Once you can do that consistently, you can change the focus to combinations and calculation. This involves a very different approach: instead of lots of easy problems, we need to solve harder, deeper problems.

Why? Because that's what these concepts are. By definition, a combination is an interplay of several different factors. You first need to recognize the potential factors (eg, pattern recognition), and then you have to put them in the proper order. This necessarily involves longer puzzles, and a greater depth means more moves to evaluate and analyze.

The same is true for calculation. If there's only one obvious move, you don't need to calculate anything; you just play the move. When you have no obvious move, though, or when multiple options look good, or when your opponent has multiple ways to react, here is where calculation shines. Once more, it involves longer, deeper puzzles.

Notice that the focus here shifts. With board vision and pattern recognition, you want fast, easy puzzles. Either you see it or you don't. With calculation and combinations, getting it right is less important than doing it right. Calculation is not just staring at the board and hoping the right move jumps into your head; it's a learned skill. If you are analyzing moves, finding all the candidates, trying to tie the patterns together, you are strengthening these muscles. If you get it right, great! If not, you have a chance to improve your thinking process. Unless the puzzle is leagues beyond your ability, the only mistake is to not try at all.

Said another way, getting a puzzle wrong is a chance to ask, "Why didn't I see the answer? Why couldn't I figure this out?" You can then figure out what you should have done and try to do that next time. Over time, if you have the discipline to keep doing this, all of these examples will coalesce into your calculation skill. It's about getting the process right, even if some individual puzzles are wrong.

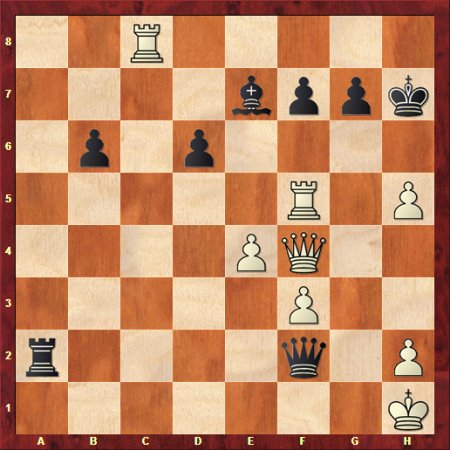

As an example, here's a position where I spent 10min calculating but couldn't find the solution. The time was still well worth it, though, and I learned from the experience. I take that every day of the week:

Link to the solution.The Role of Tactics Trainers (Alternative Heading: Why Tactics Trainers Don't Work)

All the big chess sites have some sort of tactics trainer, where you solve puzzles tuned to your difficulty. It's super simple: log in, click start, and you are taken to a puzzle. Solve it and go. Nothing could be easier.

It's also completely ineffective. Why? Because it doesn't account for the discussion above.

The tactics trainers work by assigning you a puzzle rating and lining you up with puzzles in that rating. Because these match your ability, they are too hard for the board vision and pattern recognition phases. The puzzles will take longer to solve. This may work for calculation training, but I often find the "standard" puzzle for your rating is a touch too easy for real effective calculation. Further, some sites penalize you for taking "too long" to think. Chess.com is the main culprit here: puzzles too hard for pattern recognition, but focus on speed makes it ill-suited for calculation.

When you "train" on Chess.com, I'd argue you aren't training any of the main areas at all.

To make the best use of these trainers, you need to approach them in a certain way. Clearly state at the beginning your goal: easy board vision and pattern recognition, or harder calculation focus? For vision and patterns, select a particular theme (for example, here is lichess's page), select the easiest difficulty, and do lots of puzzles. For calculation, you can use the standard modes, likely on harder difficulty settings, but ignore any speed incentives. Screw your tactics rating. It doesn't matter. We want to improve our tactics ability, not some online number.

I do want to touch on one element of these trainers: many people enjoy the "random" nature of the puzzles, where you don't know what the particular theme will be. This mimics a real game, as nobody will tell you, "Hey, keep an eye out for some skewers here." Indeed, this is true, but only if you already know all the particular themes.

Random is an excellent way to test your knowledge or to keep yourself sharp, but it's a terrible way to learn. Can you imagine if your math textbook showed you an addition question, then a multiplication one, then some algebra, then division before back to addition? This is a terrible way to learn addition! Your mind is being dragged all around, unable to focus on what matters. Do 20 addition problems in a row, learn how it works, get comfortable, and then start mixing it up. You don't start with the mix-ups!

The earlier you are in your chess journey, the less helpful the random nature of tactics trainers will be. Indeed, I did not learn tactics through online training, but through Tarrasch's "The Game of Chess." It did exactly what I have outlined: many simple examples, all organized by theme. Tarrasch was considered the great teacher of his age; he probably knew what he was doing. It certainly worked for me.

Recap and Conclusion

Have a clear goal with your tactics training. Are you focusing more on patterns or on calculation? If patterns, then use many easy problems that you can solve quickly. For calculation, use harder problems and take your time. Weaker players will get more mileage out of focusing primarily on those easy positions, but it is useful to do both. In either case, be wary of using the default "random" setting.

Indeed, I'm not saying to only do one or the other. No, that's silly. Rather, focus on one, and certainly, for any given training session, know what you are trying to improve. A random training approach produces random results. That's a recipe for inconsistency. Know where you want to go is the first step in getting there.

Great write up! Lots to consider

ReplyDelete